Around 1918, at the end of the First World War, an unprecedented cultural revival took place in Harlem. It made history and was known as the Harlem Renaissance. Writers, poets, artists, musicians, actors and theorists proudly showed what the New Negro was capable of. For the first time, African Americans felt valued and respected.

Much about that important period in black history has been published. For a long time, however, it was concealed that many of the Harlem Renaissance tastemakers were gay. It was thought that making that public would undermine the euphoria.

This essay by Rob Perrée is about this aspect of the Harlem Renaissance. Because of Gay Pride Month we re-publish this essay.

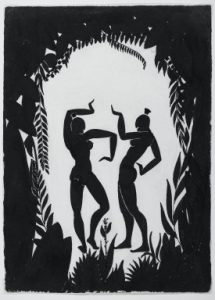

Richard Bruce Nugent, Dancing Figures, c. 1935, copyright Thomas Wirth

The Harlem Renaissance at 100

In 1923 the homosexual African American sculptor Richmond Barthé tried to gain admission to the art academy in New Orleans. It did not work. Even the help of influential white friends could not help. His skin color was an impregnable obstacle.

Richmond Barthé, Feral Benga, 1935

At the same time in Harlem, New York, the ‘Harlem Renaissance’ was taking place, with an unprecedented revival of black culture. The concept of the ‘New Negro‘ was celebrated there with writers such as Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen, with musicians such as Fats Waller and Duke Ellington, with visual artists such as Aaron Douglas and Malvin Gray Johnson, photographers such as James Van Der Zee and with theorists like W.E.B. Du Bois and Alain Locke. The fact that many of these protagonists were homosexual did not (or hardly) prevented them from playing that leading role.

Malvin Gray Johnson, Negro Soldier, 1935

Black historians, as well as a lot of white colleagues, have managed to keep the aspect of gayness/queerness out of the books for a long time. That was an impregnable obstacle for them. They felt that the representation of the African American would be negatively affected. It is only in recent years the specialists have admitted: “The Harlem Renaissance was as black as it was gay” (Henry Louis Gates).

History sometimes writes its own history.

At that time, most black Americans lived from the beginning of slavery in the south of the country. They had to work in the countryside, on the many plantations. That changed a hundred years ago. Then there was a massive migration from south to north. Poverty, lynchings of the KKK and unemployment were important factors. But there was another, more decisive factor. Elsewhere a path out of misery was offered. Especially during the time of the First World War, when industry in the North flourished. At the same time, thousands of men were called to fulfill their military service and immigration came to a virtual standstill. A large labor shortage was the result. Blacks were given the opportunity to fill the gap. Large black communities emerged in cities such as Chicago and Detroit. With its more than 700,000 new residents, Harlem grew into a kind of mecca for blacks, “a black city in the heart of white Manhattan”. For the first time they were allowed to feel that they were desired. Many got paid jobs, they lived in their own homes, they could buy their food from black suppliers, black schools provided for their education, in black churches they could practice their own religion, and they read their own newspapers. Even the civil authority was maintained by blacks ( the black policeman made his entry). It was no longer strange that a black person became rich and had her/his own house designed by a black architect. Districts such as’ Sugar Hill ‘and’ Strivers’ Row ‘are the prime and still very much sought after examples.

This development created an unyielding pride and the conviction that they themselves were capable of doing the things that had been reserved for whites up until then. Black regiments even took part in the war in Europe and were respected because of their courage and perseverance. Cynically perhaps, but it was very important for the ‘New Negro’. Being respected was a new feeling. The discrimination certainly did not disappear – those same soldiers found out when they returned home and were left to their fate – but the former slaves had found an answer to it. They were challenged to measure themselves with their white ‘masters’.

Political leaders took advantage of the new situation. Marcus Garvey (1887-1940) was one of the most influential and colorful examples. On one of James Vanderzee’s photographs he looks like an operetta figure, in his uniform with flossing and feathers, but he managed to mobilize thousands of people when he drove around like a king in Harlem. The general public loved him. His speeches make it clear that Martin Luther King and Barack Obama fit in with a long oratorical tradition. He called on his fellow countrymen to cash in on their pride by going back to Africa. That’s where they came from, that’s where they belonged. He turned against contraceptives, because that would prevent the expansion of the black race. The fact that he eventually ended up in jail because of fraud was not yet foreseen at that time.

W.E.B. DuBois, by Winold Reiss, c.1925

W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) was much less loud and flamboyant in nature. He was a professor of history and sociology at the University of Atlanta before moving to Harlem. The first black professor. His support for the Harlem Renaissance consisted of a series of publications in which he turned against racism and any form of unequal treatment (also against European colonialism). In fact, he provided a theoretical foundation. His message was embraced by the middle class and the intellectuals. Du Bois also founded the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, a social interest organization that still exists. He demanded from culture-bearers that they acted black, that they stood up in their work for the interests of black culture. Art which did not want to be propaganda found no mercy with him. It did not make him popular among all artists. Many especially young artists and writers – they called themselves ‘The Niggerati’ – demanded artistic freedom. They separated themselves more and more from their spiritual father.

His articles often appeared in ‘Crisis’, the home organ of the NAACP. That magazine had a circulation of 100,000 and as a result it had a big influence on the developments in Harlem.

Cover of FIRE!!, 1926, design Aaron Douglas/ Cover New Negro, 1925, design Reiss, Collection Walter O. Evans

Alain Locke (1885-1954), a philosopher who graduated from Harvard University, was the one who literally catalogued the cultural revival. At first in a special issue of the magazine ‘Survey Graffic’ (1925) and, in the same year, in the book ‘The New Negro’. In it he collected texts, stories and poems by Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Richard Bruce Nugent, County Cullen, Claude McKay and Wallace Thurman. He had it illustrated by the artists Aaron Douglas and Winold Reiss. He assumed that the “spiritual emancipation”, “this renewed self-respect and self-dependence” could best be read by the amount and level of literature and the art that it produced. The book would become a standard work. Later, critics would attack it because it would be too elitist and contradictory because the selection of the writers would be too personal and the underlying philosophy was too much in line with the ideas of Du Bois, meaning, too conservative. That does not alter the fact that the book goes down in history as a proof of and a successful attempt to underpin a striking and important flowering period in African-American culture.

Langston Hughes, by Winold Reiss, c.1925/Richard Bruce Nugent, Lucifer, c. 1930, Copyright Thomas Wirth

Many poems and novels were published by large publishing houses and thus reached a white readership. This was possible, among other things, through the financial support of wealthy private individuals, such as the elderly Charlotte Osgood Mason, an imposing woman that many people were afraid of, because her generosity had strict rules. The mediation of the (white) ballet critic of the New York Times, the eccentric Carl van Vechten, was also important. He had a huge network and was friends with almost all black writers. And then there were of course the ‘dressed’ dinners where writers performed for publishers and the literary salons and reading afternoons that had to generate fame among the wealthy Harlemites. Frequently read magazines such as ‘Crisis’ and ‘Opportunity’ published generously.

Cover of CRISIS, 1923, Collection Walter O. Evans

Visual artists were supported in a different way. There were several art prizes, assignments to illustrate magazines and books were numerous and it was possible to win a scholarship that made it possible for them to develop further in Paris, the cultural capital at that time. There they had encounters with the giants of French visual art.

The new spirit also found its translation into social life, especially into nightlife. That was varied, noisy, hedonistic and decadent. On 133rd street were the biggest clubs. The street was nicknamed ‘Jungle Alley’. There sounded jazz music deep into the night, played by the masters of the genre. Duke Ellington and his band performed often, Ethel Waters and Bessie Smith sang and ballet dancer Earl Tucker honored his nickname ‘snakehips’. New dances were tried out on the dance floor. The Cotton Club, Connie’s Inn and Small’s Paradise were the most popular entertainment venues. The first had the extravagant shows, in all three it was prohibited to obtain stimulants such as marijuana and cocaine. Especially the owner of the Cotton Club, Owen Madden, did not bother about that. As a professional gangster, he regularly took the law with a grain of salt. Striking in these clubs was that blacks…