In the early hours of October 25, security forces showed up at the residence of Sudanese prime minister Abdalla Hamdok in the capital Khartoum.

They said “there is a change, you will be staying under house arrest”, Hamdok recalled in an interview with the Financial Times about the military coup that knocked Sudan’s democratic transition off course and sparked global outrage.

More than a month later, the soft-spoken economist has been reinstated through what he called a “workable agreement” with the army to avoid “a catastrophic situation”. Dozens have been killed in mass protests against the military takeover. But far from quelling anger at the coup, Hamdok’s deal with the generals jeopardises support for the technocrat.

Although protests have lost some of their intensity since the agreement was inked, “the streets are saying ‘there’s no bargaining, no negotiating, no military in government’”, said Duaa Tariq, co-founder of CivicLab, which promotes civil and political rights. “Hamdok has lost the street. He has lost a historic chance to get the people on his side.”

Signed on November 21 by Hamdok and Abdel Fattah Burhan, Sudan’s top general and the coup leader, the pact restored the civilian element of the country’s transitional government, supposedly paving the way for elections in July 2023. The 14-point plan falls short of the agreement that brought both men to power during the 2019 revolution as part of a hybrid government. Under that agreement, the military and civilians shared power after the fall of longstanding dictator Omar al-Bashir.

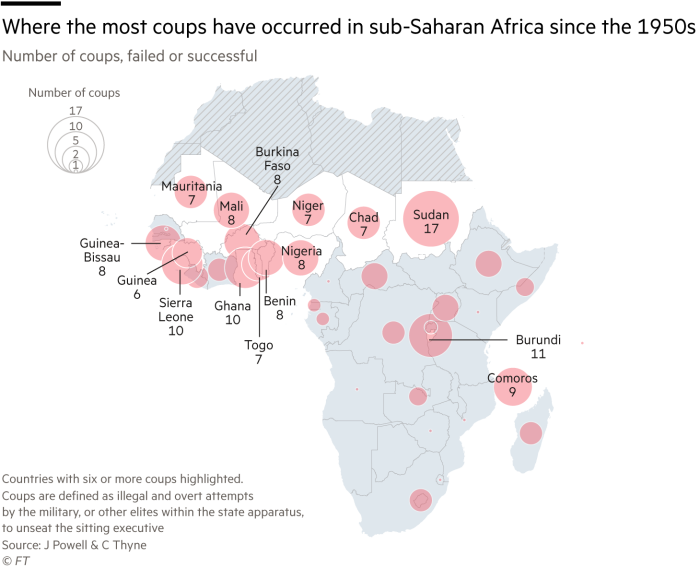

Under the deal signed by Hamdok, the military has tightened its grip, barring politicians from Sudan’s cabinet at a time when the country’s $30bn economy is crumbling. The battle for democracy in Sudan — a country that has suffered 17 coups since it became independent in 1956 — is far from over.

But protesters, politicians and activists are pushing back on the presence of the military in the transitional government.

“Whoever sheds blood is a criminal who has no legitimacy to rule and whoever drags the country into violence stands against the slogan of the peaceful revolution that was once raised,” said Amjed Farid, a former assistant chief of staff to Hamdok. “It is not possible to build the country, solve its problems, or move forward through threats and intimidation. A country is built on hope, not violence.”

Two key players behind the deal are Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemeti, Sudan’s vice-president and commander of the powerful Rapid Support Forces, and his brother, Abdul Rahim Hamdan Dagalo.

While formally deferring to Burhan, Hemeti has come to the fore as the military has tightened its grip on Sudan’s faltering transition. “I am very happy indeed, I was part of the agreement along with anyone else,” he told the FT at the headquarters of the RSF.

Thousands of protesters took to the street in anger at the coup, in an echo of the 2019 demonstrations that spurred the military to topple Bashir. At least 43 people have been killed since the coup, according to a Sudanese doctors’ committee.

Hemeti and Burhan claim neither the military nor the RSF were responsible for killing protesters, but point to some possible elements within the police. “Armed” people linked to certain political parties might be responsible for some of the street deaths, Burhan told the FT — an allegation that has been roundly dismissed by Sudanese politicians. Burhan also said 10 people were killed, not dozens, citing a preliminary investigation by the attorney-general.

“Peaceful demonstrations are already protected by law and the constitution, we have no objection, all the security forces — army, intelligence, police, RSF — all of them have very strict instructions to protect the peaceful protesters, the civilians,” said Hemeti.

These words ring hollow to the mother of Mohammed Abdarhamim, a 27-year-old computer science student, who she said was shot in the head by security forces on the day of the coup. “Our son died in the pursuit of civil government and this agreement between Hamdok and Burhan changed nothing, so unless we have the civil government that our son died for we are not acknowledging this agreement. Those who murdered my son cannot rule my country,” said Amel Abbas.

The loss of popular support is partly because the deal Hamdok signed compels him to form a government of “independent technocrats” and not politicians. Hemeti justifies this by pointing to the dysfunction of the past two years. The Sudanese economy is in crisis and inflation is running at more than 360 per cent.

“Here in Sudan, for more than two years ever day there has been a conflict with the political parties, they are always competing with each other,” said Hemeti. “During this period, we sat down, we gave our advice, we encouraged them to get together to distribute the power with all the people but they didn’t listen.”

In fact, one reason given by Hemeti for keeping Hamdok under house arrest was to prevent other politicians influencing him. “If they would have been with him, this agreement may have not seen the light of day,” he said.

Raja Nicola Eissa, a Coptic Christian, former judge and now member of the Sovereign Council that oversees Sudan’s transitional government, said that if “many problems have not been solved over the past two years, we want to correct that”.

But without a political presence in the government, it is unclear how long it can last. Siddiq Mohamed Ismail, deputy chair of the Umma party, one of the country’s largest, said “politicians should be part of the government”. Even Hamdok strikes a note of scepticism on how feasible it would be to form a government without politicians. “There is a saying that the Sudanese are either poets or politicians — and there are very few poets,” he said.

Suliman Arcua Minnawi, a former rebel leader turned governor of Darfur that is known as Minni, also helped broker the recent negotiations. He hailed the prime minister for a signing a deal: “He accepted it for the sake of his country. He is not a politician, he doesn’t have the need to be strong before the eyes of the people, he only needs to clear the road for Sudan to move forward.”

But for many, the deal quite simply is not enough. “All the people here do not believe in the deal. The deal is not accepted by the streets,” said Imad Hashim, a 40-year-old mechanic and protester, pointing to where a fellow protester was recently killed. “We won’t listen to Hamdok. Hamdok should fight for the people, not for the military. We are going to keep protesting until we have a full civilian government with no military in it — never again the military.”