PREVIEW

Two new reports investigate how political leaders are subverting constitutional rule and handing power to business cronies

Call them illiberal democracies, elective dictatorships or ‘no-party’ politics, the global tide of authoritarianism with constitutional characteristics has been welcomed, sometimes pioneered, by some governments in Africa.

Mobile telecommunications and broadband internet have ended state monopolies on information and have been taken up by activists. They have also pressured more governments to organise elections with a patina of credibility, or as a senior diplomat put it, to show that ‘an election-like event has taken place’. In many ways, the pandemic and accompanying public health and financial crises have exacerbated these trends.

Academic researchers and activists describe two processes which thrive in this evolving landscape: ‘Democracy Capture’ and the rise of the ‘Shadow State’. Both are the subject of two new research papers.* They show the different ways in which African political systems are being subverted to respond to a narrow set of private interests rather than the public will.

Democracy Capture

Democracy Capture is the process through which the ruling party uses its influence to take over – or at least compromise – checks and balances. This is the classic form of democratic decline.

Using its control of the legislature, the government passes laws enabling it to bolster its authority while the president abuses appointment powers to remove independent judges and electoral commissioners and promote pliant allies in their place.

Democracy Capture doesn’t just happen in countries where pluralism has long been under fire, such as Uganda and Zimbabwe. It is more pronounced in these states but the weakness of most many legislatures in Africa means that it is happening even in some of the continent’s more open political systems.

Due to a combination of weak party structures, a tendency towards clientelist politics, and the fact that citizens value MPs’ abilities to deliver development to the community more than scrutiny of new laws, parliaments rarely hold the executive to account.

Some National Assemblies have rejected government policy on critical issues. Zambia‘s parliament threw out President Edgar Lungu‘s ‘Bill 10’, which it was said would turn the country into a ‘constitutional dictatorship’. That was perhaps a precursor of the opposition victory in August (AC Vol 62 No 16, Rivals close as polling day nears & Vol 6 No 17, Reconciliation and a reckoning).

In other cases, Presidents have been able to marshal their own MPs and co-opt support from across party lines to pass laws that tighten their grip on power.

In Benin, the multi-party era began with the resounding defeat of authoritarian leader Mathieu Kérékou in 1991, allowing the emergence of one of the most competitive and free political systems on the continent.

After several peaceful transfers of power, Benin was rated by indices such as Freedom House as having high levels of civil liberties and political rights. Since then, the governments of President Yayi Boni and more recently, Patrice Talon, have rolled back such gains.

After coming to power in 2016, Talon used his business interests to establish patron-client ties with legislators, promoting personal allies who in many cases had little experience of politics. This gave Talon more control of the National Assembly and the judiciary, allowing him to change Article 132 of the Electoral Code, introducing tougher eligibility criteria for presidential candidates.

The new rules mean that anyone wishing to stand for president must secure the signature of at least 16 members of parliament or mayors. Talon then ensured that parties and candidates loyal to him won an overwhelming majority of legislative seats and mayoral positions, so that the opposition could not get the required number of signatures and was unable to contest the 2021 general election.

From a thriving multiparty system, Benin has been turned – in less than a decade – into a near one-party state.

Shadow States

The term ‘Shadow State’ refers to the subterranean process that often accompanies Democracy Capture. It includes the network of unelected individuals that collude with senior politicians to shape policy in their own interests and block opposition parties from taking power.

When these networks are fully developed, Shadow State is a parallel form of governance. The façade of the formal or constitutional state is maintained to legitimate the system but real power lies elsewhere.

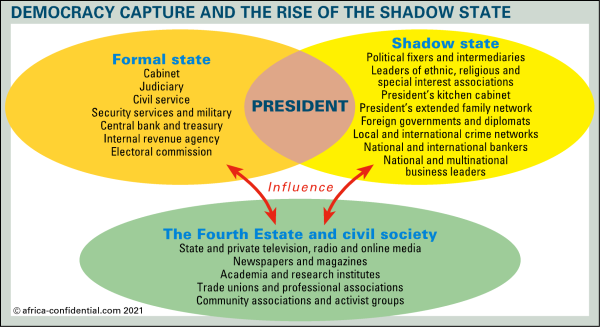

The networks that make up the Shadow State are broad and complex (see diagram, Democracy Capture and the rise of the Shadow State). They can include: business people, civil servants, political fixers, judges, military and intelligence commanders, religious leaders, directors of the Central Bank and tax revenue agencies, foreign bankers,electoral commission officials, directors of parastatal companies, media owners and family networks

Usually, the president heads the Shadow State but family members, business people and generals may also wield great power.

Shapes and structures of Shadow States differ from country to country, reflecting particular historical and economic conditions.

Countries such as Congo-Kinshasa with vast reserves of natural resources develop Shadow States that are ‘externalised’. That is closely tied to multinational companies and traders, foreign banks and international brokers.

In Congo-Kinshasa these networks overlap with organised crime and the smuggling of resources across borders. All that ensures that much of the revenue from copper, cobalt, diamonds, and oil never reaches the national treasury.

In Zimbabwe, where diamonds from the Marange fields in the East of the country have been exploited to benefit a small civil-military elite since the mid-2000s, the outcome has been catastrophic financially for the country.

What this meant in practical terms emerged when President Robert Mugabe had to form a coalition government with the opposition Movement for Democratic Change in the wake of the flawed 2008 general elections.

Zimbabwe’s need for international financial assistance led to the MDC’s Tendai Biti being appointed Finance Minister, from where he could track revenues flowing through the Treasury and those that were not.

Biti reported that diamond revenues had not made a meaningful contribution to state resources despite their volume and he concluded ‘that there might be a parallel system of government somewhere in respect of where these revenues are going, since they are not coming to us’.

In Uganda, where the National Resistance Movement government came to power as the National Resistance Army in 1986, the security forces have been key to President Yoweri Museveni‘s grip on power. Today, authority is concentrated in the Museveni family – a quasi-monarchy including his half-brother Salim Saleh, his wife and Education Minister Janet Kataha Museveni, his only recognised son Lieutenant General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, and a kind of military aristocracy underpinning it.

Although Museveni shuffles the military figures around him to remove potential rivals and promote loyalists from the junior ranks, the cohort of privileged senior military officers across the state and society has been a constant in his three and half decade rule.

Although the constitution requires them to retire their military commissions before taking up civilian roles, generals have served as cabinet members.

The politicisation of the security forces was at its highest so far in Uganda’s national election in January when Museveni’s popular rival, the youthful musician turned political leader Bobi Wine, faced comprehensive repression and intimidation. His harassment included an incident in November 2020 in which soldiers fired into crowds of Wine supporters who were protesting against his arrest, killing scores of people.

As well as preventing Wine from campaigning properly, the military cordoned off his residence as President Museveni’s victory was being announced, stopping him from contesting the flawed outcome.

It is in countries where politics have become heavily militarised along with the Shadow State system that the prospects are bleakest for free elections.

Fighting back

Democracy Capture strategies and Shadow States make national regeneration much harder because they involve taking over the institutions of law and order so they can protect themselves from investigation and prosecution. The system from which they benefit can be constantly reproduced.

In Nigeria, corrupt business people and politicians have spent tens of millions of dollars to suborn judges. According to former Supreme Court Justice, Justice Kayode Eso, this has led to the emergence of ‘billionaire judges’. They now have a vested interest in continuing to subvert the law.

These research studies into cases of Democracy Capture and the Shadow State, necessarily highly selective, point to a far wider use of such strategies by governments under recent waves of authoritarianism.

Defenders of Shadow States often tie their critics up in lengthy and expensive court proceedings. Even if these cases are ultimately lost, the process exhausts defendants and consumes resources that could otherwise be invested in mobilizing citizens against repressive practices or grand corruption.

In some countries, such as Tanzania under the late John Magufuli, the fear of reprisals was so great that no researchers…